New study shows: EV batteries last much longer than expected

Sometimes it’s about child labour in cobalt mining, then it’s about range anxiety or the collapse of the power grid if all electric cars charge at the same time – the internet is full of false statements and half-truths about electric cars and their batteries. As soon as one topic is refuted with facts or made obsolete by longer ranges and better charging networks, the next rumour is spread. One of these myths is battery ageing: used electric cars will be almost impossible to sell as the battery ages quickly, loses range and, in the worst case, has to be replaced – supposedly.

Like so many myths, the one about battery ageing has a kernel of truth – batteries age in two ways. So anyone who wants to find out more about electric cars will sooner or later come across such stories. One thing is clear: the battery is the most expensive component of an electric car, which is why the legitimate question arises as to how this affects the residual value of the car or how often electric car batteries actually need to be replaced and what financial consequences this has.

Management consultancy P3, which specialises in electric mobility, conducted a study to provide a fact-based answer and counter the battery myths. In the first step, P3 examined 50 electric cars from its own fleet and later analysed the real measurement data from 7,000 electric cars. P3 wants to use the results to provide consumers with comprehensive information to eliminate misunderstandings about electric mobility and battery life. “Misinformation can have a negative impact on the transition to electric mobility by fuelling unfounded fears and thus reducing social acceptance and market penetration of electric vehicles. Therefore, providing reliable and transparent data is crucial to provide a realistic picture of actual battery life and thus strengthen confidence in electric vehicles,” the white paper states.

State of health as the main indicator

Before we get to the results, let’s briefly clarify a few terms. The ‘state of health,’ or SoH for short, is central to battery ageing. There is no standardised definition here; in this publication, P3 refers purely to the battery’s capacity. The SoH is defined as the ratio of the current, measured capacity to that in new condition – strictly speaking, the net capacity in each case, i.e. the energy content that the customer can utilise. The gross capacity, i.e., the energy content installed in the vehicle, is higher but irrelevant here. In the end, only the energy available to the customer in the electric car counts. In other words, the net capacity when the battery is new corresponds to a SoH of 100 per cent. If the current capacity drops later, the SoH also drops below 100 per cent. The manufacturer’s warranty conditions often specify 70 or 80 per cent after a certain mileage or period of use.

For completeness, there is often talk of “calendar” and “cyclical” ageing. During calendar ageing of a battery, chemical structures in the battery cells change, even without active use. Cyclical ageing causes additional stress due to the charging and discharging of the battery. Both factors cannot be avoided entirely (more on this later) and cannot be clearly separated from each other. For this reason, the SoH definition does not include values such as the charging and discharging history, but only the capacity – which is relevant for electric cars from the customer’s point of view.

Data from over 7,000 vehicles analysed

What is new about this study is the fact that it is based on real data from vehicles on the road. In its SoH model, P3 previously made predictions about service life based on academic data and laboratory measurements – usually at cell level. The data from the electric cars adds not only external factors such as environmental influences and driving and charging behaviour but also the programming of the battery management system and the ageing strategies implemented by the car manufacturers in terms of how they stress and/or protect their batteries.

P3 took two approaches to obtain the all-important vehicle data: Firstly, 50 vehicles from the company’s own fleet were measured, the battery was examined for previous ageing, and the SoH was correlated with usage and charging behaviour. “The vehicles were selected to gain insights into as many different driving and charging profiles as possible and to identify differences between the manufacturers,” says P3.

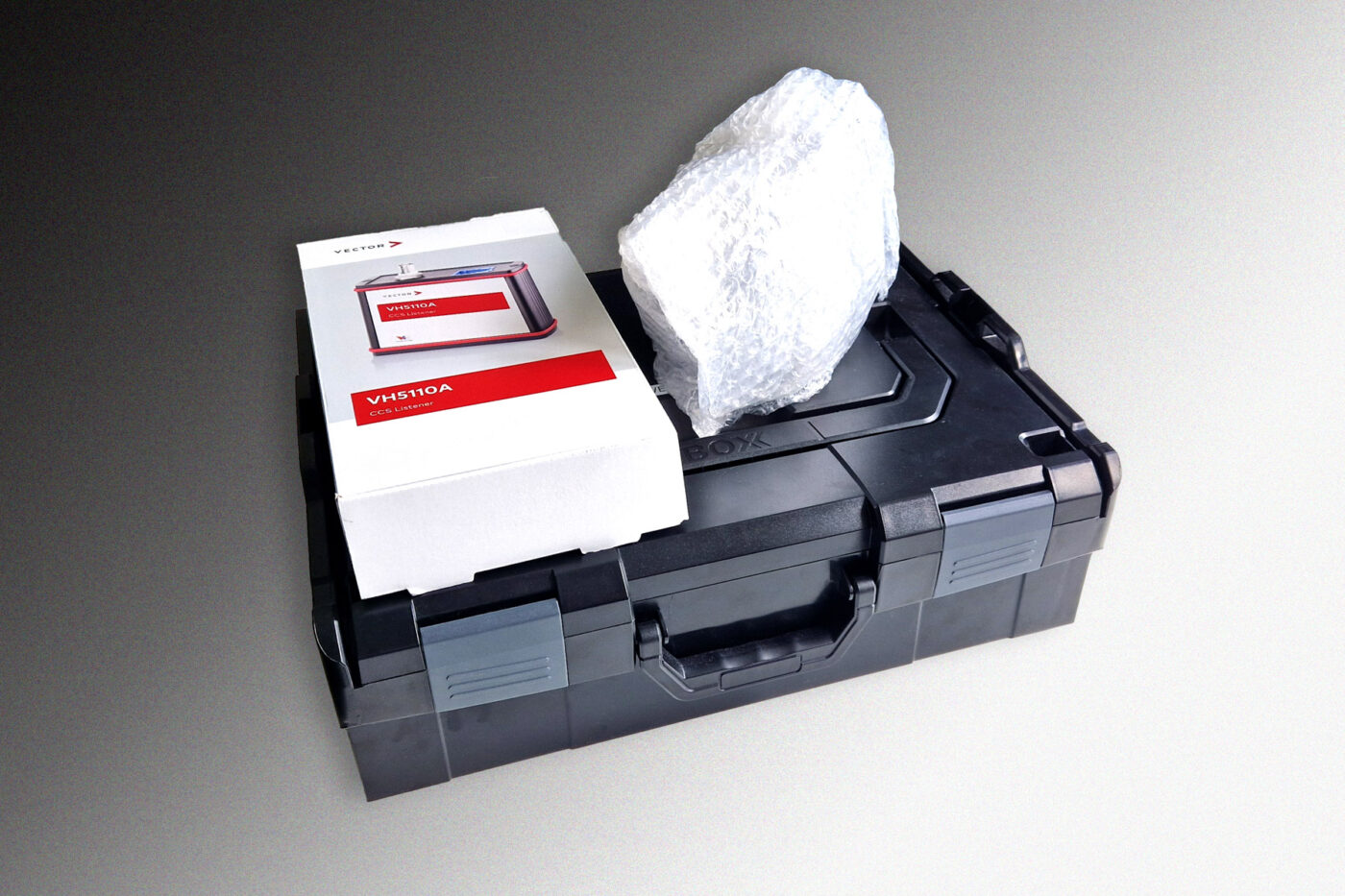

To back up these qualitative individual analyses with more quantitative data, the second step involved the Austrian battery diagnostics startup Aviloo. According to the latter, it has already carried out over 60,000 capacity tests. A brief digression: Aviloo offers two different analyses, the ‘Flash Test’ and the ‘Premium Test.’ In both cases, the so-called Aviloo Box, an OBD dongle, is connected to the vehicle’s OBD port. For the ‘Premium Test,’ the battery is charged to 100 per cent and run down to ten per cent with the dongle connected. That way, countless battery-relevant data is measured and analysed on the Aviloo servers. The ‘Flash Test’ only takes place when the vehicle is stationary, and analyses the available measured values based on the database that was set up for the respective battery type via the ‘Premium Test’.

For its analysis, P3 used the data records of over 7,000 vehicles, all of which were analysed using the ‘Premium Test’ – this procedure is more complex but also more precise. This data set also included vehicles with a mileage of over 300,000 kilometres. “This allowed the battery ageing to be assessed in more detail and more quantitatively in relation to mileage,” the white paper states. “This specifically complements the analysis of the P3 fleet and provides a broader database for a well-founded assessment.”

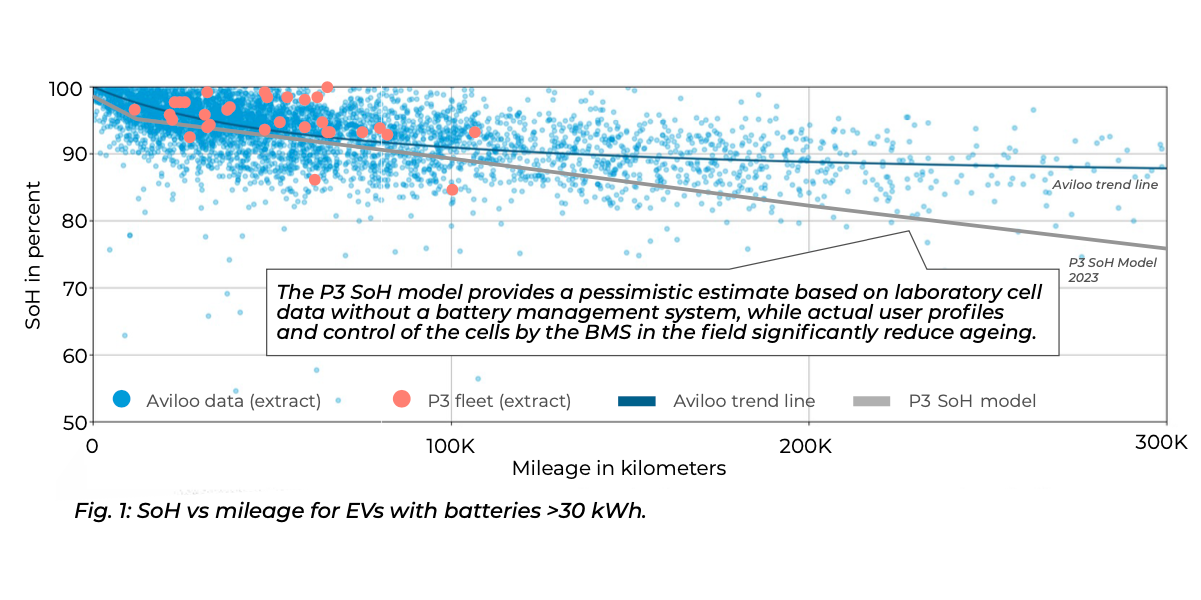

And the evaluation has a clear result: in the first 30,000 kilometres or so, the loss of capacity is accelerated, meaning that the state of health drops relatively quickly from 100 to around 95 per cent. The good news is that the real degradation decreases with increasing kilometre mileage. The Aviloo data from the 7,000 vehicles shows an (averaged) SoH of around 90 per cent at 100,000 kilometres. And after that, the trend line is almost horizontal; between 200,000 and 300,000 kilometres, it is almost stable – and is well above the 70 to 80 per cent from the battery warranty. In fact, it is closer to 87 per cent.

There is a simple explanation for the rapid SoH loss in the initial phase: a so-called SEI layer (solid electrolyte interphase) forms on the anode (i.e. the negative terminal) in the battery cell during the first charging and discharging cycles. These are deposits of reaction products from the electrolyte that always form. Depending on the vehicle and battery chemistry, this can occur in very different ways, which is why there is a wide variation in the data. However, the trend line from the more than 7,000 vehicle data sets provides a good estimate.

And the data from the 50 P3 vehicles also matches the results from the Aviloo analysis. Some of these vehicles were also used for other tests, so the driving and charging profile of these vehicles may well be more extreme than that of a company car that is primarily used for commuting. Nevertheless, their batteries have proven long-lasting: “Almost all of the P3 vehicles tested have a SoH of over 90%. It indicates that the batteries in the P3 fleet continue to perform very well despite different manufacturers, different usage profiles and intensive use.”

Another interesting finding from the more than 7,000 data sets: The field data suggests that the actual battery capacity is maintained longer than assumed under real-life conditions, especially with the often-cited high mileages of 200,000 kilometres and more. Based on the cell lab tests, the SoH model published by P3 in 2023 gave a much more pessimistic forecast for battery health. Up to around 50,000 kilometres, the laboratory model and the field data are roughly the same – above 100,000 kilometres. However, the trend lines diverge significantly. P3 concludes that the actual user-profiles and the control of the cells by the battery management system in the field significantly reduce ageing.

But how can the observed variation be explained? After all, some vehicles still have an extremely high SoH after more than 50,000 kilometres, while individual vehicles are still at 98 per cent after almost 200,000 kilometres – while others quickly fall below 90 per cent. In fact, the charging and usage behaviour of drivers and the vehicles themselves influence this, as do the manufacturers. On the one hand, the intended buffer (i.e., the difference between gross and net capacity) plays an important role in terms of size and utilisation of the buffer. That is because it can be used, for example, to reduce the noticeable ageing during the warranty period – by releasing a little more net capacity over time. On the other hand, the charging behaviour can be adjusted via a software update. On the one hand, this can be a higher charging power for shorter charging times, which leads to more stress in the cell. On the other hand, it is also possible that an update improves the control of the cells, for example, by optimising preconditioning to reduce stress during fast charging under sub-optimal conditions.

Database deteriorates with higher mileage

Two points of criticism of the data sets should not go unmentioned: P3 itself points out that the database for vehicles with over 200,000 kilometres is significantly smaller than for vehicles with lower mileage. “The reason is that there are only a few vehicles with such a long range. It somewhat limits the data’s validity for high kilometre readings and also leads to greater scattering of the data,” the study says. The “survivorship bias” must also be taken into account. After all, only high-mileage vehicles still roadworthy at 200,000 or 300,000 kilometres were measured. Vehicles no longer in use due to battery failure are not included. That may make the reliability of the vehicles appear too positive. But the big problem is that even if an electric car fails prematurely, according to the ADAC breakdown statistics from 2023, this is only occasionally due to the traction battery. “Individual cases, such as failures caused by special usage behaviour or production errors, can still occur and often occur within the warranty period and therefore rarely pose a financial risk to consumers,” P3 writes.

So, what can consumers do to improve battery health and slow down the ageing process? Roughly speaking, with careful driving and charging behaviour. A distinction must be made between calendar and cyclical ageing for a more detailed answer. Important: These are general statements. In individual cases, different behaviour is possible depending on the vehicle and battery. However, the following P3 recommendations will not damage the battery.

In the case of calendar ageing over time, the main factors are temperature and state of charge. When not in use, batteries prefer low to medium temperatures below 25 degrees, according to P3. Too high a temperature (over 60 degrees is mentioned) is a “driving force for chemical reactions, which leads to accelerated degradation of the capacity.” However, the vehicle or battery management can also help here, as our technical deep dive into the VW Group’s PPE platform shows. The charge level at which an electric car is parked over a longer period of time is also important. A higher charge level means a higher voltage in the cell – which accelerates ageing over a longer period of time. P3 recommends parking the vehicle with a low to medium charge level (ten to 50 per cent) for very long parking periods.

Gentle driving and charging behaviour help the battery

Temperature also plays a role in cyclical ageing, i.e. utilisation, but in a different area. If the battery is used, it should be neither too hot nor too cold. That applies to (fast) charging and driving. High currents (fast charging, heavy acceleration, driving at high speed) are generally not conducive to SoH, but especially at extreme temperatures. In other words, moderate driving behaviour with constant, low speeds and infrequent fast charging at medium temperatures would be ideal – and with a low depth of discharge, i.e. if the charge level remains between 20 and 80 per cent. It is not the end of the world if you deviate from this in individual cases (because fast charging is also required along the motorway in winter). However, a predominantly gentle driving and charging behaviour can slow down battery ageing.

The survey also shows that real battery ageing rarely breaches the terms of the battery warranty. The standard warranty for EV battery systems is currently over eight years or 160,000 kilometres, with the first manufacturers going up to 250,000 kilometres and ten years. Lexus even offers a warranty extension to one million kilometres or ten years on the (admittedly not widely used) UX300e. The battery thus generally lasts much longer than the warranty or other parts of the vehicle.

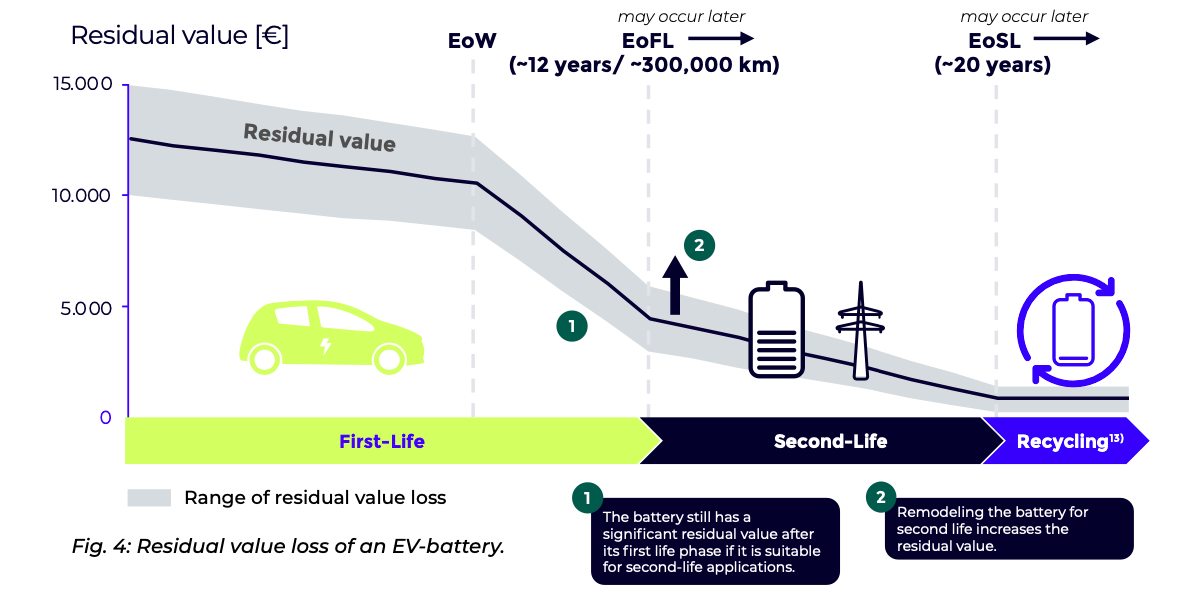

With the long service life, a second use of the battery after the ‘first life’ in the vehicle is, of course, also possible, for example, as stationary energy storage – the ‘second life.’ Only after this second use, i.e. around 20 years or more, does a battery go into recycling. At least that’s the model.

To answer the question posed at the beginning about the residual value, it depends heavily on the current utilisation phase. Within the manufacturer’s warranty period, it is naturally higher than after the warranty has expired, even if the battery in the vehicle is still functional. The residual value decreases as it is no longer replaced or repaired under warranty. “Within the warranty period, the loss in value is heavily dependent on ageing and the remaining capacity,” P3 writes. “After the warranty expires, a greater loss in value is to be expected. At the end of the first lifetime, depending on the cost of new batteries, the battery may still have a significant residual value through a second use.”

p3-group.com (white paper for download)

26 Comments