New ICCT study fuels debate on heavy-duty vehicle emissions

As the European Commission prepares to present a new draft law on commercial vehicle emissions next week, the International Council on Clean Transportation is providing new material for the debate in Brussels. We asked the ICCT directly what their findings mean for future purchasing decisions.

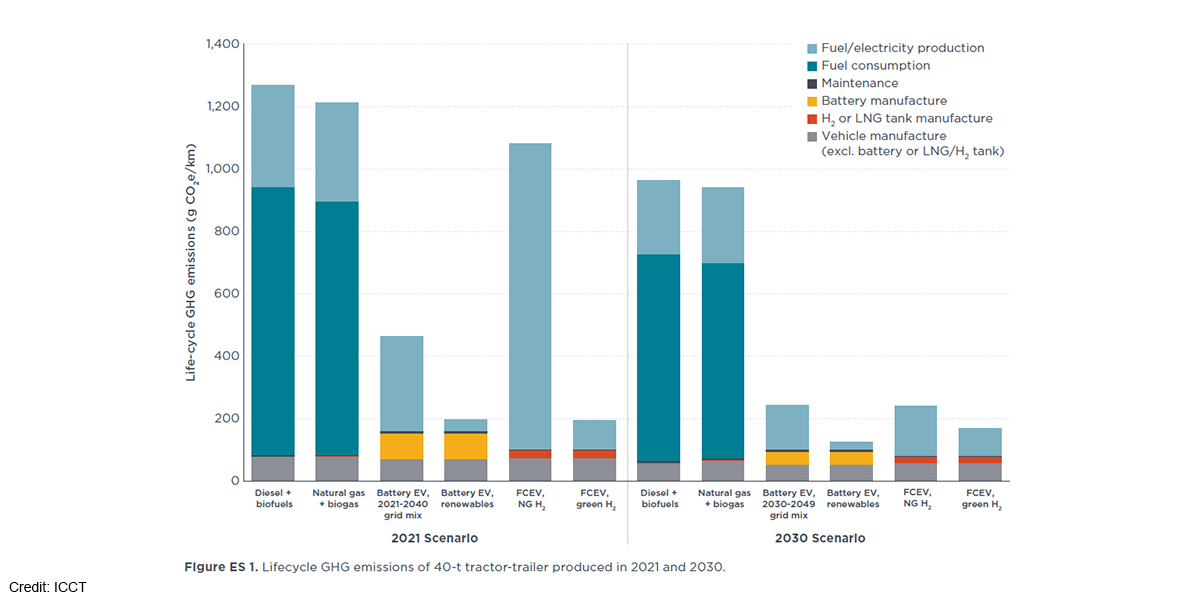

To be blunt, the new ICCT study clearly states that battery electric powertrains are superior to all other fuelled types in saving greenhouse gas emissions. This, says the ICCT, “indicates a clear path to decarbonisation of the sector”. In doing so, the results go on to show that battery electric models achieve the greatest emission reductions among all vehicles, even assuming the EU’s current electricity mix, which is known not to be too green yet but will continue to improve over the lifetime of the vehicles.

The life cycle is the key to the environmental organisation’s findings – more on that in a moment. The ICCT’s results are not entirely surprising; other studies and institutes have come to similar conclusions, also for passenger cars. Nevertheless, the ICCT report comes in time to support the EU Commission’s expected draft legislation. Leaked documents, seen by the German Tagesspiegel Background, show that the EU is concentrating on battery-electric solutions and hydrogen; e-fuels, for which some German politicians wanted a loophole to be left open, play no role in the Commission’s draft. Fire brigade and military vehicles could be the only exception.

With regard to upcoming purchase decisions, the ICCT’s programme manager, Felipe Rodríguez, told electrive clearly: “Environmentally conscious fleets can rest assured that they are making the right decision in procuring battery electric trucks today. On the other hand, those betting on low carbon fuels should revise their decarbonisation strategy.”

***

Coming back to the ICCT paper. The results may provide vehicle manufacturers and operators with more indicators for their next investments. Whether this is also an indication to abandon the Euro 7 standard altogether – a step Daimler Buses has already publicly called for – is left to the operator. The ICCT’s Rodríguez took a balanced view when speaking to electrive. It was true that the study shows that battery-electric trucks and buses are already better for the climate, he said, “yet this does not mean we cannot expect improvements in combustion engines. Diesel and electric trucks will coexist for the next two decades as we fully transition to zero-emission powertrains. Truck makers will still profit from selling millions of new heavy-duty diesel engines in the coming decades, and Euro 7 can ensure they are as clean as in other parts of the world.”

Diesel vs battery-electric and other vehicles

Diesel reliance is, of course, the nature of the market today – most heavy-duty vehicles still run on the fossil fuel and account for about a quarter of transport emissions in the European Union. Consequently, the ICCT analysis puts the current “best-in-class” diesel models against their natural gas and zero-emission alternatives to offer a “comprehensive picture of the life-cycle emissions on a fully harmonised basis”. What is relatively new is that the analysis takes a dynamic approach, moving from today’s fuel and electricity mix and technology (baseline 2021) to 2030, when electricity and technology will have advanced.

The researchers also look at the entire lifespan of a vehicle, which turns out to be the decisive factor for BEVs always coming up first in ecologic potential, even when taking a not entirely green electricity mix and the still carbon-intense manufacturing processes of electrified trucks into account – we will get deeper into that but below is the easy version to get behind the ICCT’s thinking.

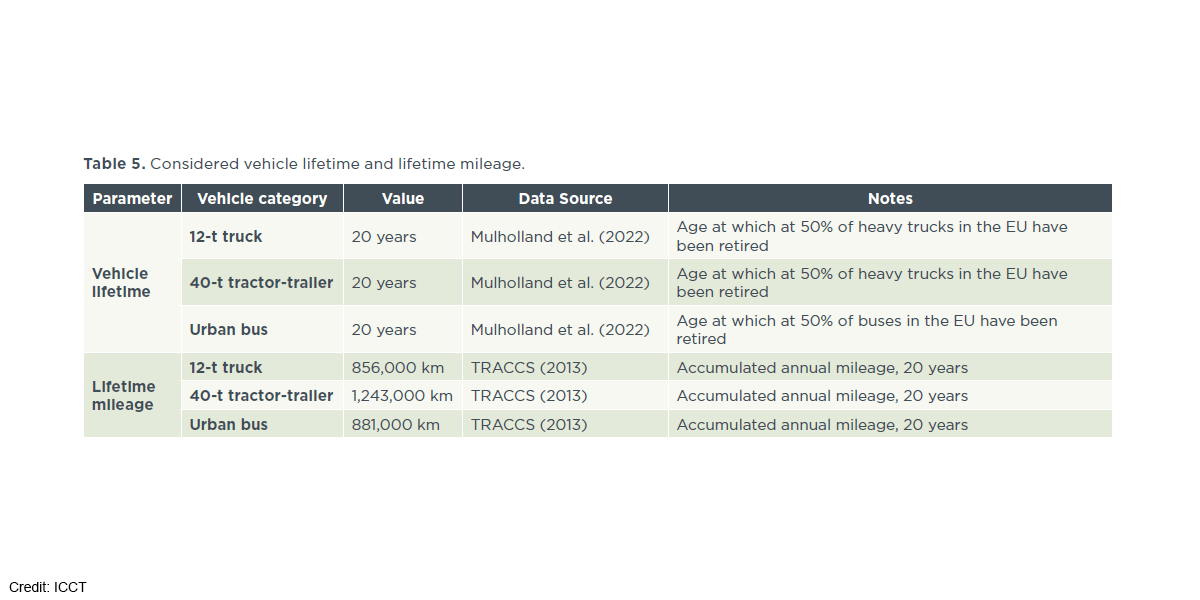

Starting from the base, i.e. the vehicles, the ICCT categorises a standard truck in the (unladen) 12-tonne and 40-tonne segments as well as a city bus. The vehicle types were aggregated using market and manufacturer data, i.e. the 12-tonne truck, for example, was identified using the manufacturer specifications of the six best-selling trucks in this segment, which account for 92 % of sales in Europe, according to the ICCT.

The “fuels” included in the study are electricity, hydrogen, natural gas and diesel. It remains interesting to note that the analysis finds battery-electric power superior in its emission-saving potential over all other fuels, including hydrogen and natural gas, despite the still partly dirty energy mix.

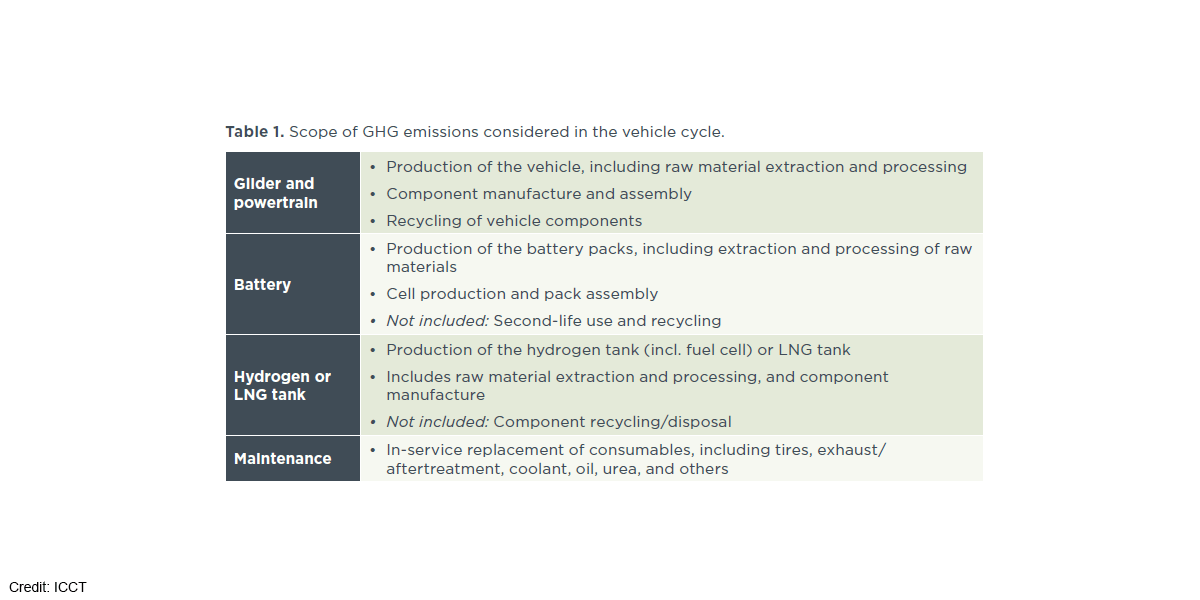

What is more, the researchers come to this conclusion by looking at the entire life cycle of a vehicle, from cradle to grave, yet do not consider recycling or second-life scenarios, which may drive further GHG savings in future.

At the same time, the manufacturing of a truck does not entirely define its green credentials. More decisive is the life on the road and the fuel it uses during that lifetime – in the study, the ICCT assumes a running time of 20 years and mileage from 856,000 km (12 t truck) and 1,243,000 km (for 40 t truck).

“The problem is not the factory but the road,” says Nikita Pavlenko, the ICCT Fuels Program Lead. “The high greenhouse gas intensity of driving a truck during its life offsets the GHG emissions generated during manufacturing or the production of the fuel or the energy it consumes.”

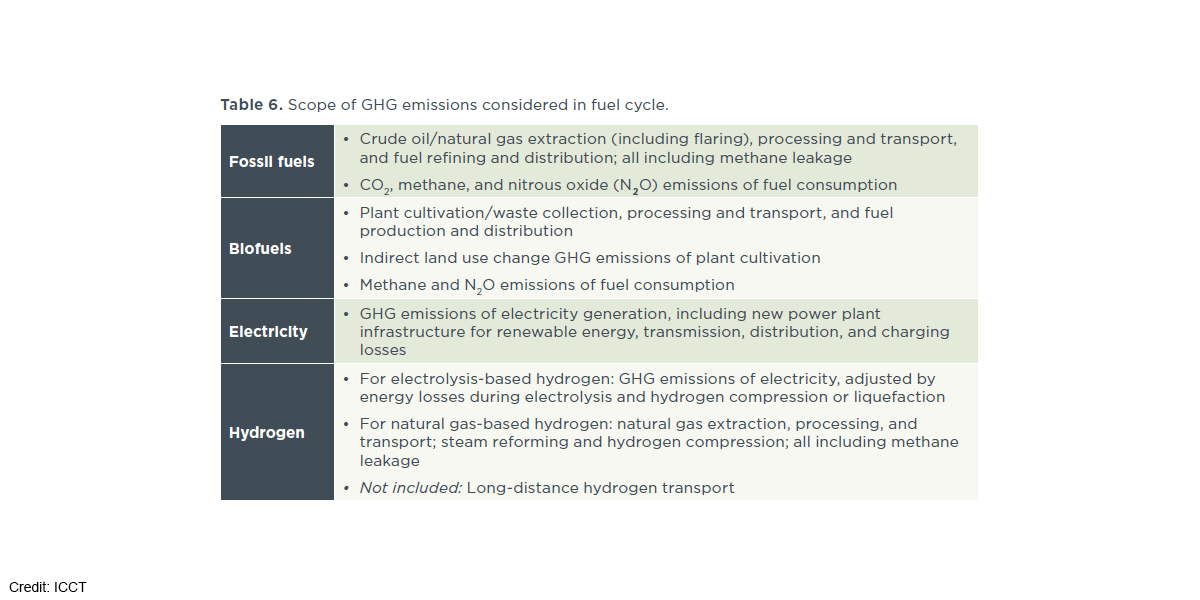

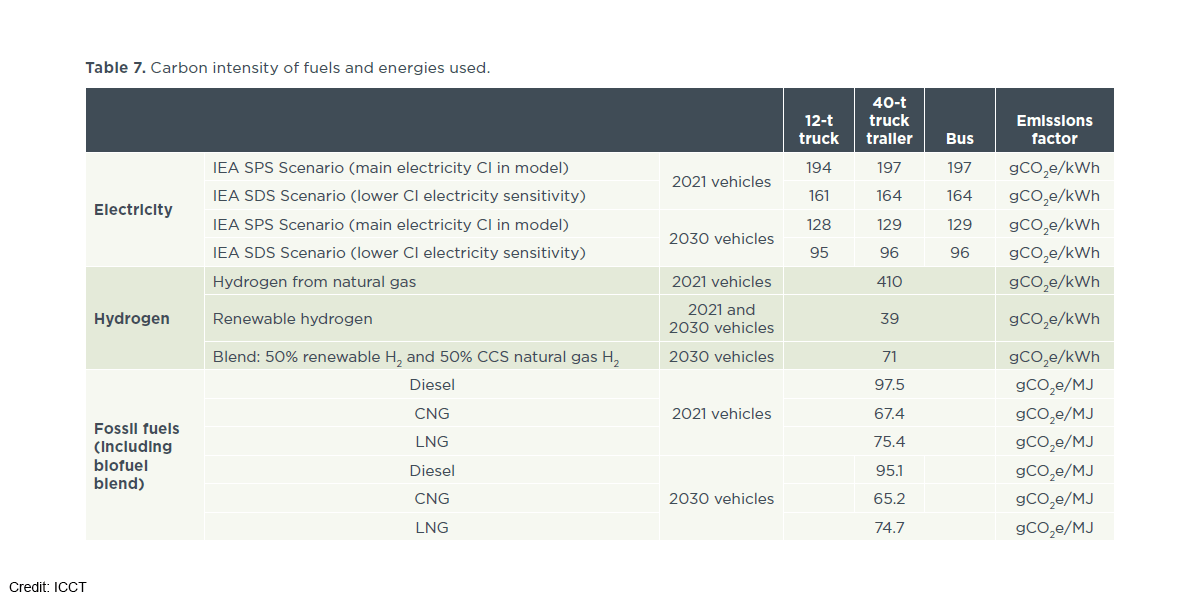

This brings us to the much-discussed energy mix or fuel cycle in the case of non-electric vehicles. The ICCT here takes a measured approach and includes said 2021 and 2030 baseline.

Assuming the current electricity mix in the EU, battery-electric trucks emit 63% less GHG emissions than diesel over their lifetime. If using only green electricity to make and power a truck alone, life-cycle emissions are up to 92 per cent lower, according to the ICCT.

Moving towards the 2030 scenario, the ICCT includes further decarbonisation of electricity generation, as outlined in the IEA’s World Energy Outlook. The electricity mix will also steadily improve due to the EU requirements to expand renewable energies. Said electricity also informs the carbon intensity estimates of vehicle and battery or tank production in the case of FCEVs.

“Our study addresses the uncertainties surrounding the share of emissions in all stages of the vehicle’s life. It shows that only battery electric and some fuel cell electric trucks can meet the climate targets in the sector,” adds Pavlenko.

Again, this goes back to the service life emissions. For diesel and natural gas trucks, the consumed fuel accounts for over 90% of their lifetime emissions, according to the ICCT. Thus, the higher vehicle and battery production emissions of battery electric trucks are “far outweighed” by their high energy efficiency and the relatively low emissions during electricity production, ICCT sums up.

But what about hydrogen vehicles?

For FCEVs, hydrogen generation remains essential since the study finds “that the greatest climate impact produced by trucks and buses over their whole life comes from the use or fuel consumption phase, not from the extraction of raw materials, construction, or maintenance”.

This fuel consumption is why FCEVs currently come behind battery-electric solutions and exhibit rather moderate savings over diesel vehicles. The ICCT analysis concludes that fuel cell trucks and buses powered by hydrogen have 15 to 33 per cent lower emissions than comparable vehicles with diesel engines.

This comparatively low figure (vs 63% in BEV today) is due to hydrogen being produced primarily from fossil natural gas. With green hydrogen, the balance is up to 89 per cent more favourable and very similar to its BEV counterparts (92% with green electricity). So, the ICCT says hydrogen can be a clean fuel but is still generated mostly from natural gas.

And, natural gas got a slap from the organisation. In the study, commercial vehicles powered by natural gas hardly perform better than diesel trucks. For a 40-tonne articulated truck, the ICCT even calculates slightly higher emissions than for a diesel vehicle. This is due to methane, which is emitted during the operation of the vehicle as well as during the extraction and delivery of natural gas and thus counts towards the life cycle assessment. The ICCT concludes that even small emission savings through the use of natural gas are virtually null and void when the short-term climate impact of methane emissions is taken into account.

It is worth noting that the ICCT also took a conservative approach to battery-electric vehicles, thus disarming arguments often made in the debate, such as the resource- and emission-intense sourcing of (raw) materials for battery cells. Taking the battery as an example, the ICCT analysis accounts for a battery replacement happening once in a truck’s life span of 20 years (based on Volvo estimates that batteries last 8 – 10 years). As before, the ICCT assumes that both production and electricity will benefit from technological advances and market trends already underway – however, excluding effects like recycling and energy density.

Therefore, there is a price to this assumption, at least in the largest trucks – one battery replacement increases the battery manufacturing emissions for the largest battery electric HDV. “This methodological choice, in conjunction with the comparatively large battery considered for the tractor-trailer, results in the 40-tonne tractor-trailer generating the highest GHG emissions associated with battery manufacturing for all three HDVs,” the researchers state.

The 40-tonne estimates include battery packs of 900 kWh in 2021 and 700 kWh in 2030, enough for an average range of 500 kilometres. The range of the bus and smaller truck is 250 -300 km, with required battery capacities of 300 kWh in 2021 and 250 kWh in 2030.

The ICCT notes in its conclusion that this effect will likely lessen within the decade due to declining battery costs in conjunction with likely increases in battery densities, but has not yet included these effects in the above result.

On the same note, battery recycling is likely to reduce the GHG emissions impact of batteries significantly further. “Due to uncertainty regarding future recycling processes, however, we exclude the corresponding GHG emission credits from this assessment,” writes the ICCT.

Are hydrogen fuel cell vehicles green (enough)?

This brings us to the most commonly used argument for hydrogen as a way to decarbonise the heaviest-duty vehicles. Here the ICCT is cautious, already when choosing fuel-cell trucks over diesel HDVs. To achieve “meaningful” GHG savings over the vehicle’s lifetime, the upstream hydrogen production must incorporate additional renewable electricity or CCS. “We find that using fossil natural gas without CCS will, at best, result in very minor savings compared to diesel,” so the ICCT.

Emissions of GHGs from FCEVs are also exacerbated by the production of both the hydrogen tank and fuel cell in FCEVs. The findings vary based on the capacity of the hydrogen tank and mostly come from the energy-intensive production of the hydrogen tank. For the purposes of this study, the ICCT assumed the storage system for gaseous hydrogen to be a series of smaller tanks linked to provide the necessary storage.

At the same time, the ICCT let us know that as with BEV batteries, for FCEVs in particular, the source of the hydrogen will have a much larger impact on these vehicles’ total life-cycle GHG emissions than the upstream manufacturing GHG emissions.

Yet again, since fuel is required to move the truck over its lifetime, hydrogen will have a harder time for some time to come, even if manufacturing becomes more sustainable. “Increasing energy efficiency is the game-changing factor in shrinking the carbon footprint of battery electric trucks compared to the rest of the technologies,” says ICCT Program Lead Rodriguez. “These models become the cleanest option even if the source of electricity is not fully clean. This is not the case for hydrogen trucks, which can become a promising option in the future if hydrogen is produced from a 100% renewable energy source. Today, their capacity to reduce emissions is still limited.”

As for synthetic fuels (e-fuels), the ICCT notes their inefficiency – they need five times as much electricity for their production as battery-only propulsion, and this is not taking other harmful factors in their production into account.

In the current draft of the European Commission, e-fuels should only be used to operate already registered vehicles in a more environmentally friendly way or to power emergency and military vehicles. Any new vehicles should have to do away with combustion engines.

The draft law can still be changed until its presentation, planned on 14 February.

theicct.org (download ICCT study), theicct.org (factsheets in English, German, and Spanish)

0 Comments