Which policies are most effective to decarbonise transport?

Transport for under 2 degrees, or short the T4<2° project, published a study today looking at the decarbonisation of transport in line with the Paris Agreement. We took a deeper dive at how experts interviewed rated the effectiveness and likelihood of climate policies.

***

First to the general findings of the white paper, which the World Economic Forum, German GIZ and Agora Verkehrswende associations just presented on behalf of Germany’s Federal Foreign Office (AA) after working on it for almost two years.

The researchers identified ten “key insights” that policymakers across the world may take as a guide when looking to decarbonise their transport systems. None of them was entirely new. Take, for example, the realisation that transport can only be decarbonised if coupled with transitions to renewable energies or, that it requires more ambition for a chance to come close to the goals agreed at COP21.

Still, the scope of the study was to add qualitative depth to the on-going debate. The researchers relied on interviews with 346 participants from 56 countries, including those that receive official development assistance (ODA) and economically stronger nations. The applied “foresight methodology” comprises a systematic literature review on transport scenarios and 56 qualitative interviews with senior experts primarily from the transport and energy sectors. Subsequently, the researchers conducted a two-stage Delphi survey, which they describe as a “structured, iterative group facilitation technique” applied in forecasts. 290 international experts from the transport and energy industries participated in the first round of the survey; 103 returned for round two.

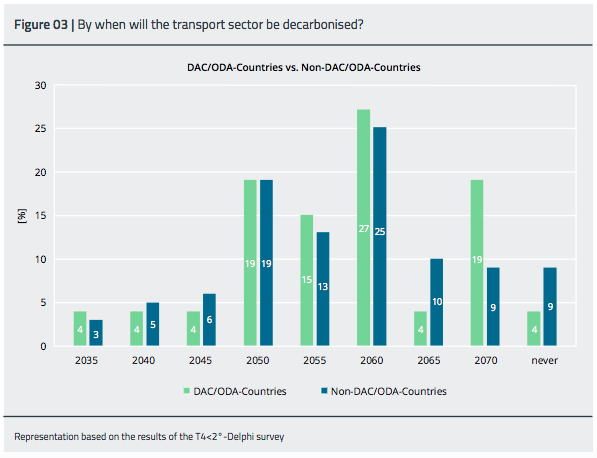

To start with the basics – the majority of respondents believe the full decarbonisation of the transport sector is possible by mid-century. For the study, this refers to the rather large period between 2040 and 2060. Most targets set by countries envision the turnaround for 2040 or 2050, on paper.

There is also unanimity that actions (or commitments) may look different in nations at varying stages in their development. But, the experts stressed that any action has to happen simultaneously, so there is no time to wait for any one country.

Still, when implementing various infrastructure policies, the panel at the live presentation emphasised the finding, that there is a chance for developing nations to “leapfrog carbon-intensive technologies” also by investing in measures that do not “lock them in” to the dependency of fossil fuels.

Of course, the study also discusses hard-fact regulations. The call for and belief in more regulatory action was more pronounced with experts from developed countries. 70% of them ranked it second (47%) or first (23%) when wanting to decarbonise transport. In developing countries, 69% of respondents ranked it second (31%) and third (38%); an additional 19% ranked it first.

Interestingly, the participants agree that transport decarbonisation must include a shift of focus from just regulation or even incentives for specific technologies to encourage behavioural change. So when asked whether a policy should influence behaviour or technology, a vast majority of the interviewees, 85% from developing countries and 79% from developed countries agreed that behaviour has a crucial role to play.

This was echoed in the general understanding that “There is no technological solution to a societal problem,” as Christian Hochfeld of Agora summarised at the live presentation. In short, ideally, people need to change their transport habits, deliberately or not.

When it comes to single policies that are being discussed globally, the majority of 79% of the experts chose measures that influence the price of fuel, such as a carbon tax as most effective. 77 per cent of participants then consider the forced phase-out of combustion engines as the second most effective measures for decarbonising the transport sector, before the introduction of zero-emission zones.

Of the experts interviewed, 47% believe that this phase-out has to start immediately; more than one-third of the experts believe that it should start in 2030 by the latest. This means that 80% of the participating experts agree that a forced phaseout must start within 10 years, concludes the study. They also recommend defining a strategy for a (global) policy-driven fossil fuel phase-out.

Whether this will be possible was another questions, and only 25% of interviewees believe that a forced phase-out is likely to be implemented to a sufficient extent, with an even smaller share of 19% of experts in developing countries.

The picture is different when looking at the measures seen as most likely to be implemented. These are led by fuel economy standards of the kind the EU and other regions are bringing in, with 56% of the experts placing them among the three most likely measures, followed by a carbon tax or fuel pricing with 51% and zero-emission vehicle zones with 47%.

That is for the stick. Turning to the sweeter carrot, the incentive-based intervention valued by 80% of the experts as the most effective policy instrument to decarbonise the transport sector is an investment in public transport. However, only 52% of experts rate this investment as the most likely instrument to be implemented.

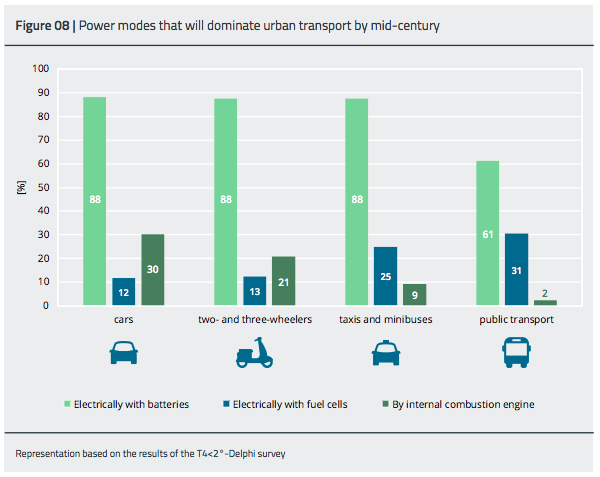

Alongside public transport, there was a look at urban mobility and which modes of transport and drives will play a part. When asked which of the two options for electrification will dominate, battery technology or fuel cell technology, experts expected battery-electric mobility to take the lead. Also when it comes to minibuses and taxis, says semi-public transport, experts see almost no room left for internal combustion engines.

The image is largely the same in rural areas; only the respondents see a slightly larger share of fuel cells due to the long distance that may need to be covered.

All participants also agreed that sharing would have to play a major part. At the same time, 88% of respondents from developing countries and 80% from developed countries expect that the remaining cars in the transport system will be individually owned rather than shared or pooled. Again here shows the need for behavioural change on the way to a decarbonised transport sector and, so finds the study, calls for policies and interventions that will make car-sharing and pooling more likely to happen.

t4under2.org (study as pdf), t4under2.org (policy brief)

1 Comment