Myth busting: Battery recycling does work

The battery of an electric car is often denigrated as rolling hazardous waste in circles still favouring the combustion engine. We were able to convince ourselves of the opposite at the specialist firm Duesenfeld that is disposing of the myth – Battery recycling works deep into the cell. It is only down to politics to define a legal framework for a recycling cycle.

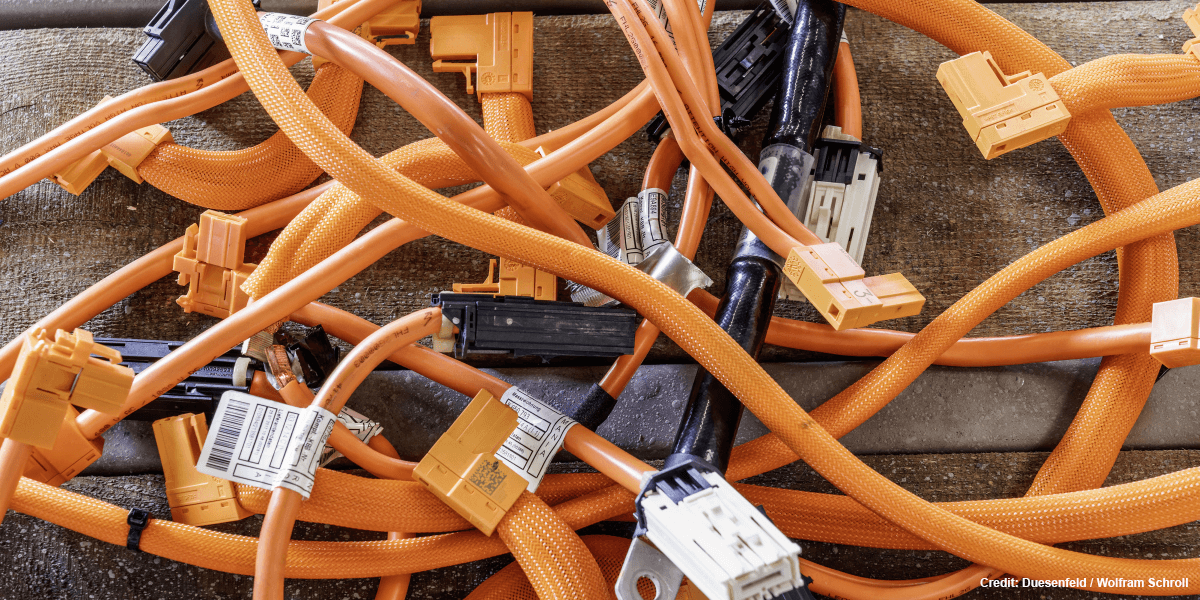

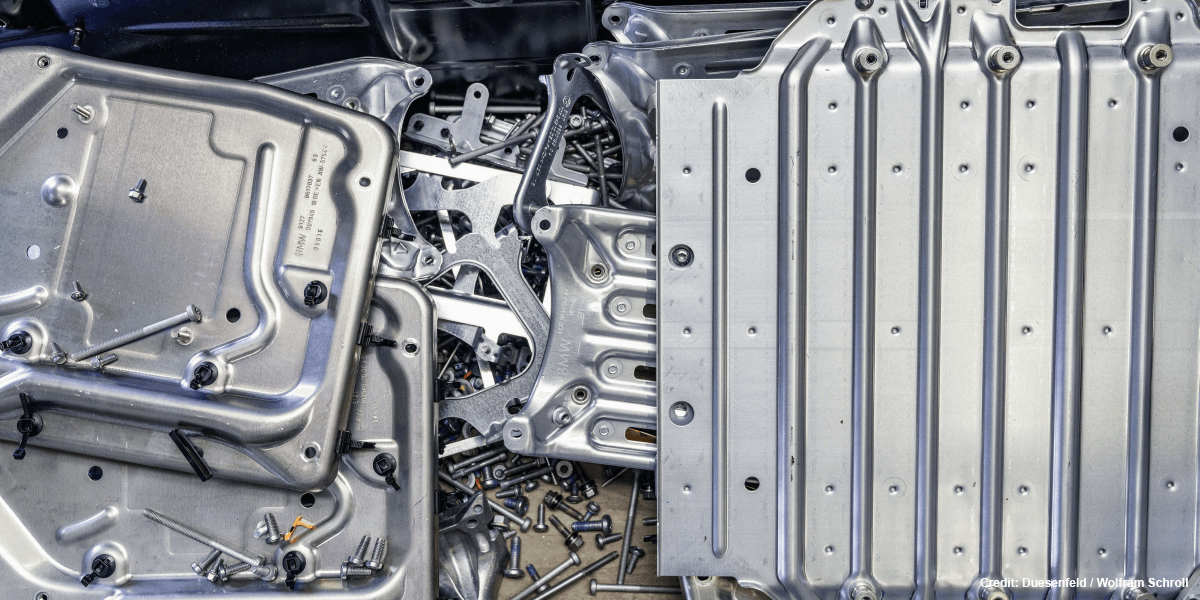

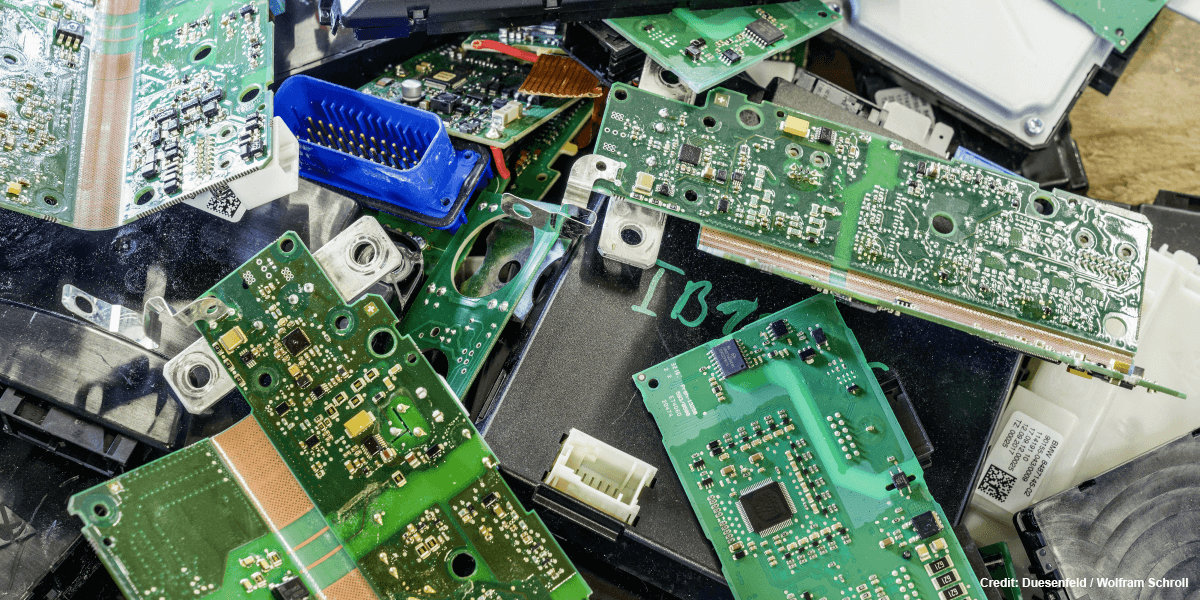

Metals over metals everywhere: A battery system consists of steel and alloy, lithium, copper, cobalt, and nickel. In addition, there are other materials such as plastics for insulation or liquid electrolytes. A mix weighing several hundred kilograms per vehicle. And one that could be valuable at some point. Therefore, an industrial recycling network must be set up for obvious reasons such as environmental protection, conservation of resources and, in the long run, also from a cost perspective.

It takes many years before the traction battery of an electric car finally breaks down if you take into account refurbishment and second use, for example as a stationary storage device. At some point, however, the recycling of an electric car’s most important component will have a massive impact. So the goal of recycling must be the most effective recovery and reuse possible.

Anyone interested in electric mobility knows the polemics and crude theses about lithium-ion batteries. It is true that dealing with them is by no means trivial or risk-free as anyone handling large amounts of energy should always be careful. Christian Hanisch, managing director, partner and visionary at Duesenfeld, is well aware of this. The editorial staff of our parent site electrive.net visited the recycling company based only 13 kilometres away from Volkswagen’s battery production hall in the German town of Braunschweig.

Mobile recycling technology saves high costs of logistics

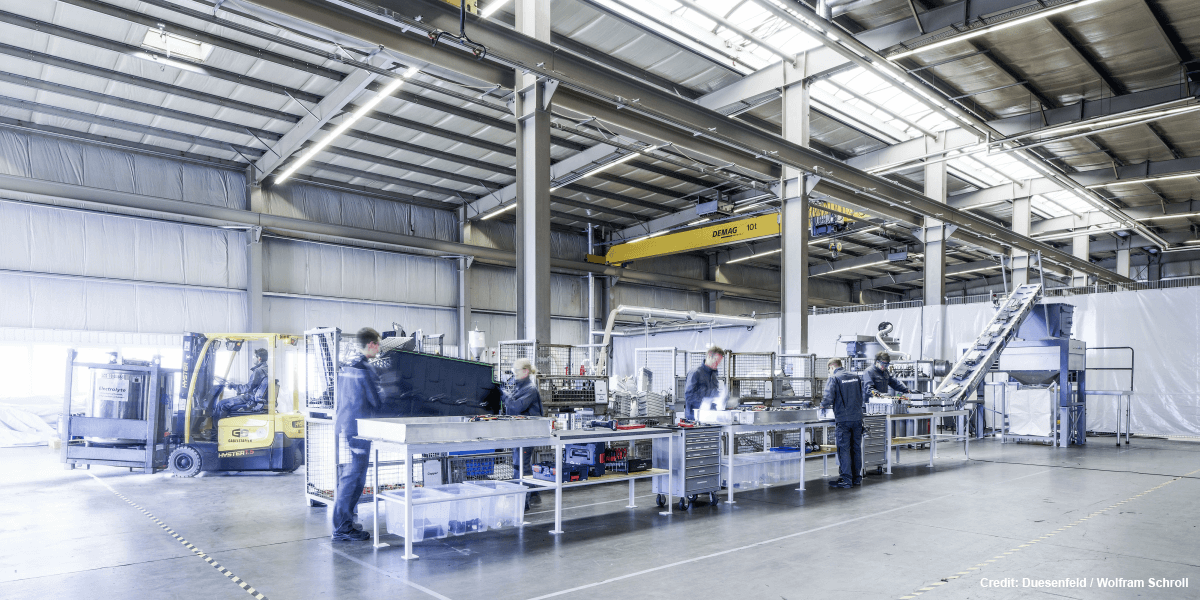

On the one hand, Duesenfeld is exemplary for the current state of recycling, because some processes resemble those of the industry giant Umicore from Belgium. On the other side, Hanisch has decisively innovated: The result is a considerably reduced energy input, therefore an improved CO2 balance, a high recycling efficiency as well as the possibility of moving the recycling technology. Such decentralised recovery is useful, among other things, because it saves costs of logistics that are usually high due to the hazardous nature of the process (high voltage batteries classify as dangerous goods).

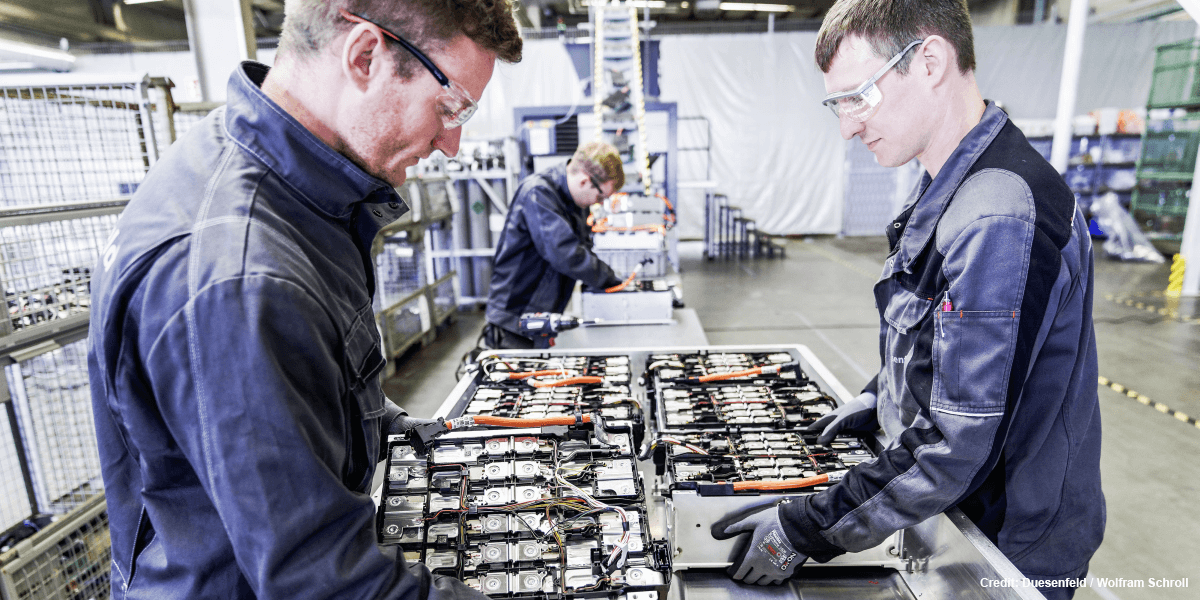

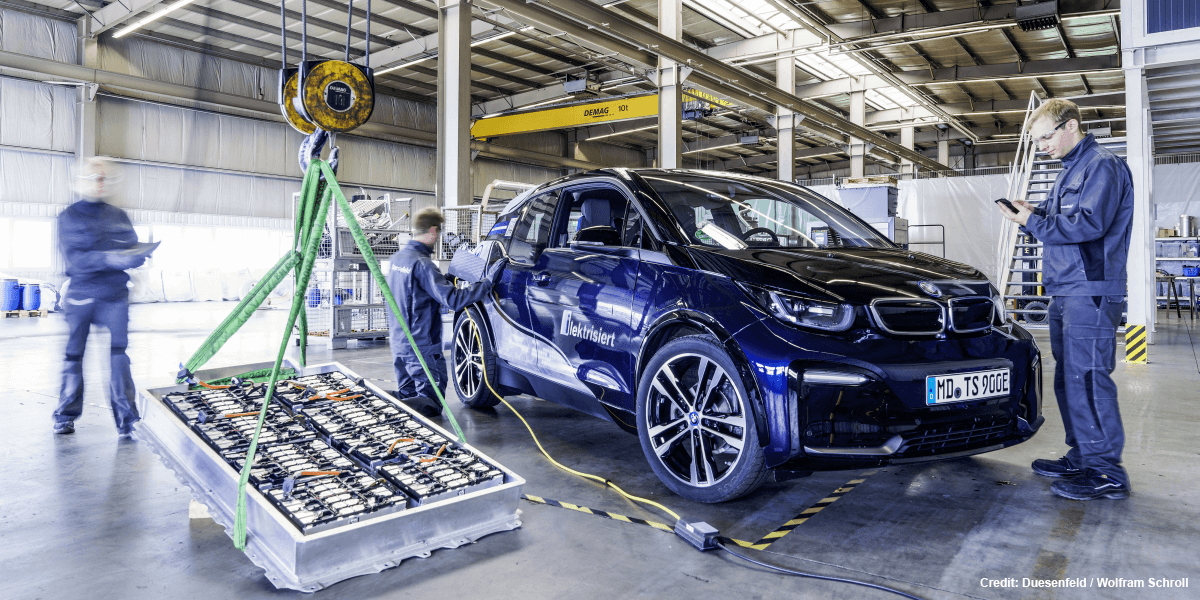

At Duesenfeld, the industry service electrive.net witnessed the dismantling of several BMW i3 batteries. They first have to be deeply discharged with the battery management system switched off for this purpose. By the way, the residual current is used to support the facility. After discharge, workers dismantle the batteries manually, and until here, the steps are still the same as those at other recycling companies. The crash-resistant outer shell with further holding structures, cables, the cooling circuit, and the modules can be dismantled with a simple tool and end up in mesh boxes sorted by type.

This is where the differences at Duesenfeld begin: many companies now use so-called thermal decomposition in a highly secured furnace. At 450 to 500 degrees the cells’ valves burst open and the critical electrolyte burns abruptly; perfect separation of the remaining materials is now more difficult.

Test recycling with residue analysis

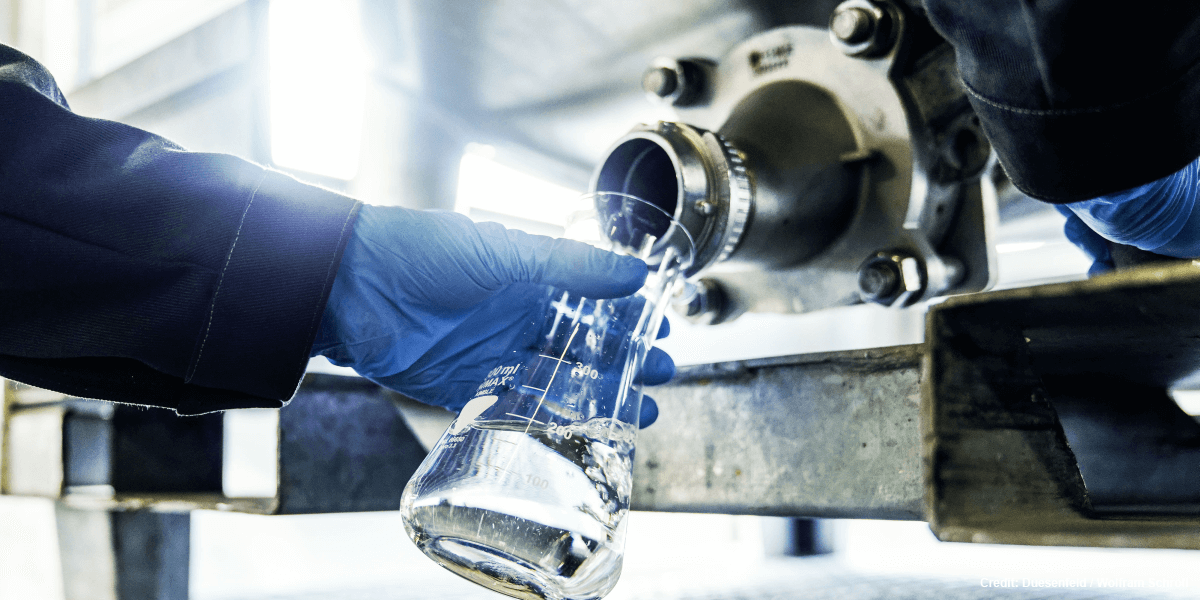

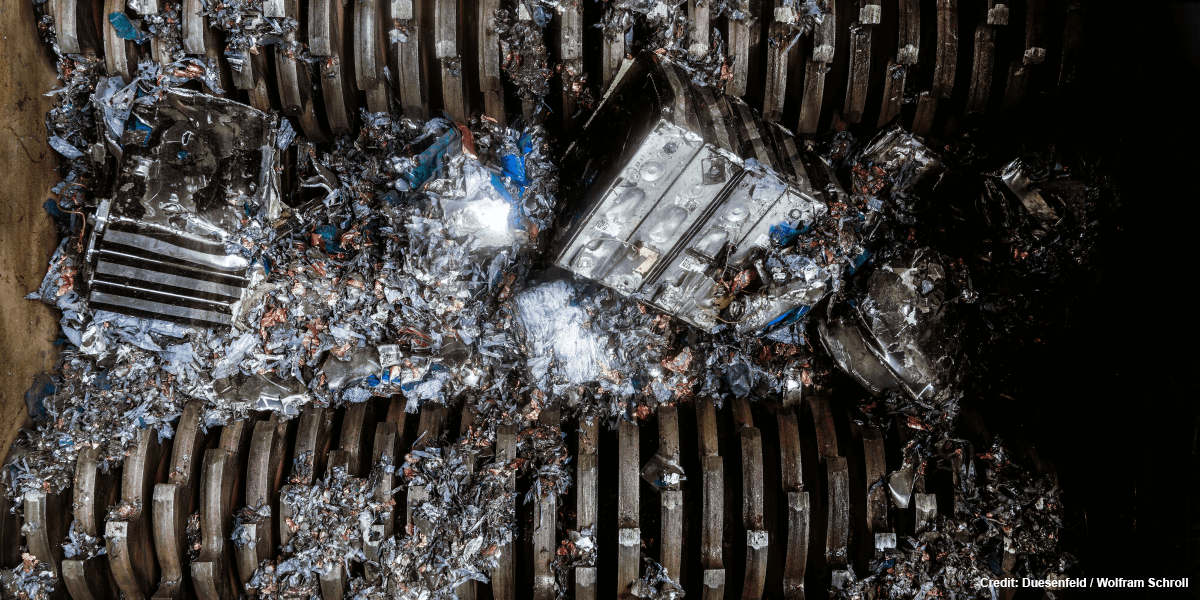

“We work with mechanics instead of temperature and crush the entire module in an inert atmosphere,” explains Christian Hanisch of Duesenfeld. The shredder contains nitrogen gas, which prevents further chemical reactions. The pressure is then significantly reduced, which first evaporates the liquid electrolyte and then recovers it through condensation. In addition to the grinding shredder, the electrolyte flows into a container.

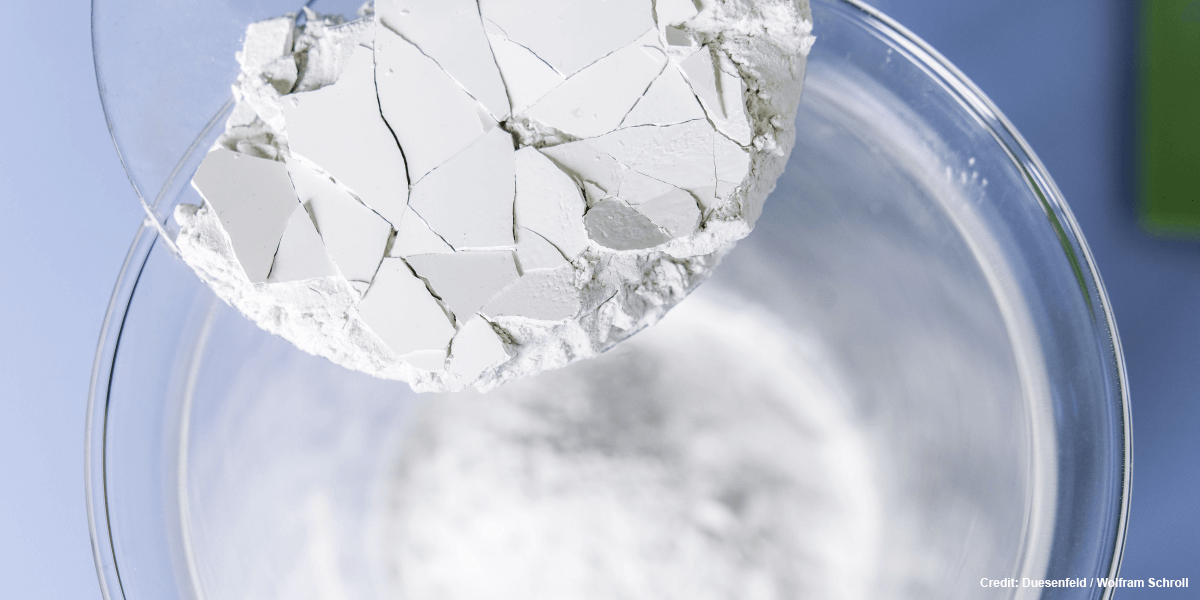

The remains of the battery module and the cells are now dried and uncritical. Duesenfeld then separates the remaining mixture by proven processes such as magnets or air. The chips of the separator foil, the ferrous metals, the non-ferrous metals such as alloy and powder from lithium as well as cathode residues with nickel, manganese and cobalt remain. According to Christian Hanisch of Duesenfeld, this black powder could soon be processed “by a hydrometallurgical process into lithium carbonate and sulfates of nickel, manganese and cobalt”. This way, most of the original battery could be retained for further use. Duesenfeld will not tell who from the automotive industry has asked the company to have ten tons of batteries dismantled as a test and to have the evaluation presented to them later. However, they let through that we are talking about international and big names.

Legal recycling quota must drastically increase

It is part of the sometimes disappointing reality of life that recycling is not yet worthwhile despite rising resource prices. It is still cheaper to produce new lithium or cobalt. However, as demand will increase radically and countries of origin increasingly use their bargaining power, the EU should drastically raise the minimum recycling rate of only 50% by weight. China wants to obligate manufacturers of electrified vehicles to take back and recycle used batteries. In the summer of 2018, China also selected 17 cities and regions to launch a pilot programme for the recycling of used electric vehicle batteries. With BMW, Northvolt and Umicore, at least the first technology consortium for the joint development of a complete value chain for electric car battery cells has been set up in Europe as well. Audi and Umicore are also developing a closed loop for recycling high-voltage batteries from electric cars.

Conclusion

The high use of resources in traction batteries has long been recognised as a problem. One way to improve is the continuous development of cell chemistry and battery systems towards ever higher volumetric and gravimetric energy density. Due to the high raw material costs, this happens virtually automatically. At the same time, a recycling network must be set up that functions on an industrial scale. This requires tightening the legal framework to not only protect the environment but also to relieve the car industry and electric vehicle owners.

Reporting by Christoph M. Schwarzer.

3 Comments