Urban Infrastructure – Part 4. LONDON: How to keep moving the masses by all means?

Incentives vs. prohibitive measures

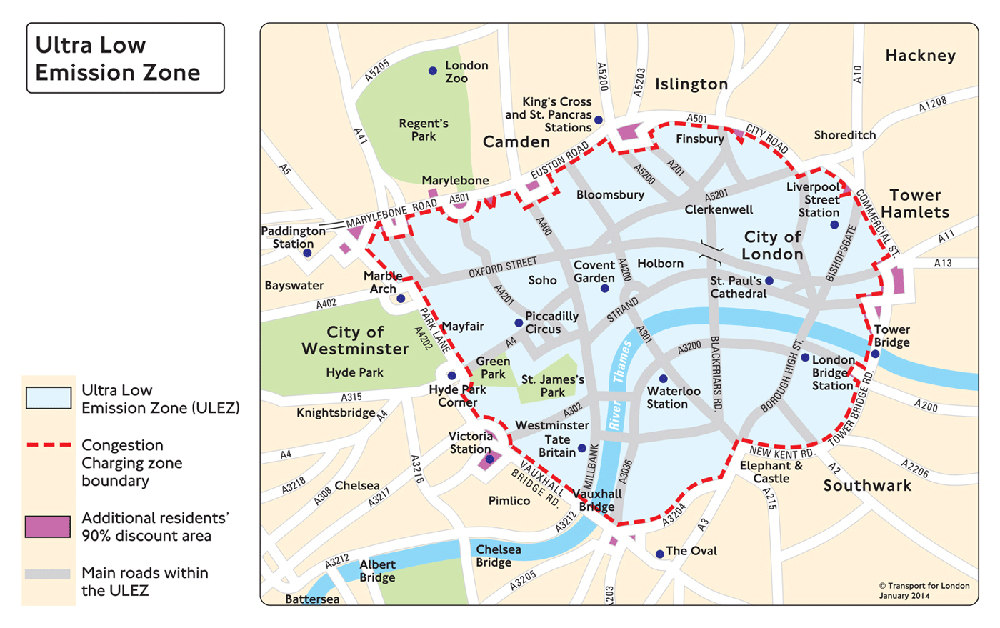

To get a grip on both congestion and air pollution as a consequence, London first introduced the congestion charge for entering the city centre in early 2003. It’s a measure only a few other cities like Stockholm have copied, while others are still looking. London’s Congestion Charge Zone (CCZ) remains among the largest in the world and is on a fast-track for extension by 2019, if Mayor Sadiq Khan gets his will. Formerly called CCZ, it is now dubbed the Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ), a positive twist of terms and reflection of technology available, like new energy vehicles called ULEVs in the UK.

“I have been elected with a clear mandate to clean up London’s air. The previous mayor was too slow on this issue, the government has been hopelessly inactive and it’s Londoners who are suffering as a result.”

Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan of the Labour party

Khan, who declared he wants to become the “greenest mayor” London has seen, started by rebranding existing schemes and has public opinion on his side. He proposed to expand the area where the congestion charge applies to the North and South Circular. On top of that, he put forward an extra charge for polluting vehicles called the T-charge (T for toxicity). It linguistically raises the issue to a moral level – who wants to be seen in a car labelled “toxic” after all?

The mayor’s plan finds widespread support among his electorate. A consultation by City Hall had 15,000 responses, more than any other consultation before. Air pollution affects all Londoners, thus 70 percent believe the ULEZ should be expanded by 2019, rather than by 2020. Another 81% support the T-charge in addition to the congestion charge, so driving into London during business hours in an older vehicle will soon cost as much as 21.50 GBP a day. The results also indicate widespread support for Khan’s call for a diesel scrappage scheme, which the British government has declined so far.

Does a congestion charge help?

Despite the charge, the problem of congestion remains. All you have to do is walk down Oxford Street with red double-decker diesel buses roaring, lined up like train coaches and black cabs squeezing in and out. The ULEZ successfully priced out private cars, however. The number of people rushing into central London in their own car in the morning was reduced by half between 2000 and 2014, and now concerns only about one in 20 people.

Still, traffic numbers remained the same for numerous reasons. The introduction of private hire services like Uber and increased amounts of delivery vans, to name a few.

“Traffic in London has slowed to pre-charge speeds. In 2003, vehicles moved at an average of 10.9 mph in the inner city, yet in 2015, the average speed was 8.3mph.”

Transport for London (TfL)

At the same time, the allocation of road space decreased and also accounts for traffic deceleration. Streets have been closed or speed limits lowered due to infrastructure and construction projects, like CrossRail, or Cycle Super Highways.

Another factor is pressure from residents to reclaim the side streets, increasing stress on key veins. Their opposition was successful because of a characteristic specific to London: only about 5% of the city’s road network, including major crossings, are under central control by Transport for London (TfL). The rest of the road belongs to London’s 33 boroughs, the districts. And, councils tend to listen to the local people they represent.

Consequently, TfL and the mayor have tried to relax the roads and to move people to cycle, walk, or use public transport – successfully so. TfL reports a net shift in mode share of 13 percentage points away from the private car between 1994 and 2014.

Another act of moving the masses differently and clear the air is the Low Emission Bus Zone (LEBZ). Buses, as a mechanism, can be guided relatively easy. London’s red double-deckers also have symbolic value, as the former Mayor Boris Johnson knew too well. His successor Khan has again expanded the scheme. As member of the Labour Party, he counts less openly on publicity but on cohesive efficiency, as he intends to send the greenest buses on the worst polluted routes, i.e. the outer boroughs. The mayor also said he wants TfL to procure hybrid or zero-emission double-decker buses from 2018.

“TfL now operates 73 electric buses making it the largest electric bus fleet in Europe, and one fully electric bus route with 51 single deck electric buses. Around 2,000 hybrid buses accrue to about 20% of the fleet in London. In addition, there are eight zero emission hydrogen buses operating and TfL is trailing inductive charging technology.”

Mayor of London’s office

Another contestant for space on London’s streets, and one that serves the public albeit privately, is the taxi. Different from other European capitals, London permits officially licensed Black Cabs and private hire cars, so-called mini-cabs or Ubers nowadays. Since the introduction of Uber, the number of hire cars in London has increased by approx. 25,000, but has not lead to a similar increase in traffic. Reportedly, newly registered Black Cabs must be able to drive on battery power alone by 2018. Private hire cars must be hybrid by then and fully battery-electric by 2020. Uber is already trialling a 50-strong electric car fleet with intent to expand.

Where is London going?

Public as well as semi-public transport in the British capital is becoming increasingly electrified and is likely to reflect on the private sector. In wealthy cities, such as Singapore or London, electric vehicles could account for two-thirds of all cars on the road by 2030, a report by McKinsey & Co and Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) showed. It listed stricter emissions regulation, falling technology costs and more consumer interest as reasons. Consultants also pointed out that a “pure product-ownership model” may become obsolete, as transport turns into a service.

In London mobility is already mixed and provided as a service. The UK capital is prone to innovation and under enormous pressure because space is scarce, so the city may well have to be at the forefront of shared transport in all its forms, and it is likely to be electric.

Author: Nora Manthey

“I have been elected with a clear mandate to clean up London’s air. The previous mayor was too slow on this issue, the government has been hopelessly inactive and it’s Londoners who are suffering as a result.”

“I have been elected with a clear mandate to clean up London’s air. The previous mayor was too slow on this issue, the government has been hopelessly inactive and it’s Londoners who are suffering as a result.”

0 Comments