Urban Infrastructure – Part 2. STUTTGART: There is trouble in the air.

How do electric cars get cleaner energy and cities better air? The new series Urban Infrastructure from electrive.com highlights the different strategies with which cities in Germany and Europe develop infrastructure for electric vehicles. Our second stop takes us to Stuttgart in the south of Germany – a city that is literally suffocating from its own automotive success story and needs sustainable mobility almost more than any other city in the country. Award-winning journalist Michael Ohnewald was born in the region and takes a closer look an area that “is so begrimed with soot that there is no way around taking action.” At least the know-how is already there.

How do electric cars get cleaner energy and cities better air? The new series Urban Infrastructure from electrive.com highlights the different strategies with which cities in Germany and Europe develop infrastructure for electric vehicles. Our second stop takes us to Stuttgart in the south of Germany – a city that is literally suffocating from its own automotive success story and needs sustainable mobility almost more than any other city in the country. Award-winning journalist Michael Ohnewald was born in the region and takes a closer look an area that “is so begrimed with soot that there is no way around taking action.” At least the know-how is already there.

Stuttgart does not make it easy for drivers – and drivers are not making it easy for Stuttgart. That pretty much sums up the dilemma that the southern German city is in. Stuttgart has a bigger fine dust problem than any other city in the country and generally takes the lead in terms of congestion. On average, drivers spent 73 hours sitting in traffic in and around Stuttgart last year – eight and a half hours more than in 2014.

And trouble is not just brewing along the major road axis, but also in politics. That is when it comes to the question of how to deal with the problem or at the very least contain it without biting the hand that feeds them: meaning, without upsetting prominent economic players in the region. Just how much influence the automotive industry has became apparent when a local politician chose a Tesla Model S as a company car. The problems began as soon as she took office. Conclusion: don’t mess with car manufacturers on their turf.

Since then, two hearts have been beating in the chests of local politicians. On one hand, the car must not lose its status in the cradle of mobility. It is, after all, responsible for much the economic prosperity in the region that well-known companies such as Daimler, Bosch, Mahle and Porsche call home. Many suppliers and more than 190,000 employees directly depend on the well-being of the automotive industry there. On the other hand, the air of the valley in which Stuttgart lies desperately needs cleaning up. That is the logical and responsible thing to do, as well as what the EU and local citizens are calling for.

One of the major problems is that cars and other mobility products are not manufactures in the living room, but in factories and companies somewhere around the city, to which workers have get. There are some 165,000 companies located in the region and some 900,000 people there commute to work. Needless to say, that creates a lot of fine dust. For ten years now, Stuttgart has not been able to reduce fine dust particles in the air to an acceptable level – which obviously had been defined because fine dust can cause severe illness or worth. Even the European Commission is tired of hearing excuses and is looking to sue Germany – using Stuttgart as an example.

That increases the pressure, especially since the city is ruled under a green flag. Stuttgart’s mayor Fritz Kuhn is a member of the Green Party, as is Winfried Kretschmann, himself head of the German federal state of Baden-Wurttemberg. And this area of all places is so begrimed with soot that there is no way around taking action. And if not, the clean Swabian image and household budget could seriously suffer, as the European Commission could inflict six-digit fines – per day!

Against that backdrop, Stuttgart is working on a package that aims to combine economic and ecological aspects. In a first instance, it is testing the so-called fine dust alarm system. Based on metrological data form the German weather service, it can predict on which days an atmospheric inversion pushes down on the basin, keeping fine dust in. The environmental office then issues a warning and asks commuter to please leave the car at home. Unfortunately, very few do. But at least the fine dust alarm resulted in everyone talking about air quality in the region.

If the system doesn’t work, Stuttgart will need to start imposing legal measures. Especially since some residents have already gone to court to demand for cleaner air in front of their door. They want concrete traffic restrictions and driving bans from 2018; also because the current voluntary model is not really bearing any fruits. Only two to seven percent of commuters listened to the town hall’s appeal not to use the car on critical days. Meanwhile, the mayor’s office has to on one hand balance people who want to use their car whenever they please (and are often quite vocal about it), and on the other, residents and environmental groups who are certain that bans and restriction are the only way to go.

Fine dust and NO2 levels that exceed the legal limit cannot only be found at certain parts of, but across the entire city. The Neckartor in the city centre might be the most well-known example. Emission levels there shot above limits for a total of 72 days last year. Measures have been put in place to reduce traffic in that part of town on critical days – but will that be enough? Stuttgart’s mayor wants to do more and is pushing the expansion of public transport and EV uptake. Fritz Kuhn himself takes an electric two-seater to and from his appointments and all new cars purchased by the city have to be electric from now on. “No one can pretend that air is not his business,” says Kuhn. “Especially in Stuttgart, there many people who own more than one car. chosing an EV as their second vehicle would already a valuable contribution. For me, it’s not a question of incentives but responsibility.”

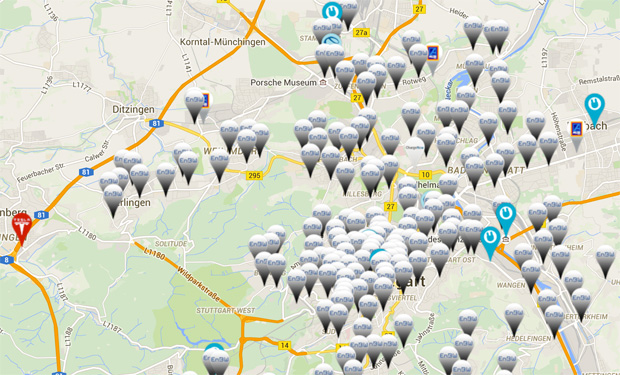

That of course begs the question: how is electric mobility doing in the region? In terms of charging infrastructure, the metropole is definitely on the right path. With 384 charging points, Stuttgart has more places to plug in than any other German town. The federal state of Baden-Wuerttemberg counts 1,115 public chargers (but only comes in second to North Rhine-Westphalia).

In other terms as well, the region hopes to offer electric mobility a setting that it can flourish in. In April 2012, the “LivingLabBWe,” founded by the State Agency for Electric Mobility and Fuel Cell Technology and the Business Development Stuttgart, became one of Germany’s four showcase projects for electric mobility. A total of 34 federally funded initiatives have been brought to life that looked at electric mobility from different angles and put it to the test in real life. That did not result in a path-breathing movement, however.

At least Stuttgart has acquired a lot of know-how on the subject. One project focused on the installation and operation of charging infrastructure in Stuttgart and surrounding areas, putting in place the world’s largest electric carsharing fleet. A total of 500 Smart Electric Drive from car2go (Daimler AG) can be rented spontaneously and left at one of EnBW’s 500 charging points. Moreover, customers of utility EnBW receive a charge card which they can use at any of the company’s EV charging points. Usage is paid hourly based on three different tariffs. People with a prepaid charge card pay 5 euros/hour, for example. Frequent users can chose to pay a monthly base fee of 7.90 euros and benefit from cheaper tariffs at the charger that are based on the car’s charging capabilities. Moreover, EnBW cooperates with other charge point operators across Germany, allowing users to plug in at roaming-partner stations as well.

This is just the beginning and not the end. Not by a long shot. People in the Stuttgart region have high standards when it comes to mobility, after all.

Another project that made a lot of waves was a field test with 500 electric scooters and just as many private test persons. The so-called “electronauts” set out to test electric mobility in Stuttgart in day to day life. They were given scooters that they could use at their leisure and charge at EnBW stations across the city while they went shopping, to the cinema or the hairdresser. The year-long pilot was Germany’s largest test fleet to date.

Progress has also been made in terms of pedelecs that are directly funded through regional programmes. There are a total of 14 e-bikesharing stations in and around Stuttgart that commuters and tourists can use as a direct addition public transport. The goal is that by making it easy to switch directly from a local train to an e-bike, more people will eventually leave the car at home. Moreover, the bikes only cost a maximum of two euros for the whole night, hopefully motivating people to take a pedelec from work to go home and take it back the next morning. Alternatively, bikes can be returned at any station, making the system easier for tourists to use.

It is safe to say that to the pressure as a result of people’s expectations of its Green Party led government, a lot is happening is the region. Which is a good considering the ever rising levels of harmful emissions there. That is also why the current state government wants to kick off a new future-oriented offensive to make the conurbation a centre and model for sustainable mobility. They now have five years to make it come true.

Text: Michael Ohnewald

Translation: Carla Westerheide

Picture credits keyvisual:

© morena / fotolia.com (background)

© Gunnar Assmy / fotolila.com (car)

© sester1848 / fotolia.com (city limit sign)

0 Comments