Urban Infrastructure – Part 1. HAMBURG: Soft sounds from the harbour.

How do electric cars get cleaner energy and cities better air? The new series Urban Infrastructure from electrive.com highlights the different strategies with which cities in Germany and Europe develop infrastructure for electric vehicles. We start out with Hamburg, home to journalist Christoph M. Schwarzer. He talks about a well thought-out approach – as well as a dilemma, which Hamburg faces vicariously for other cities.

Urban Infrastructure – How EVs get cleaner energy and cities cleaner air. A multi-part local report about EV charging and H2 filling stations.

The northern German city of Hamburg is a proud metropolis. People here are open-minded by tradition and the number of residents keeps growing. Some 1.8m people will soon live next to the Elbe and Alster River. In other words: the city state is thriving – also thanks to its port. It is Europe’s third largest and bestows a certain wealth on the city that is also a German federal state.

The filth emitted by large vessels powered by heavy fuel oil does not change the fact that road transport also has an emissions problem. Despite the high measured values alongside the city’s streets, Hamburg does not have a low-emission zone (LOZ). But considering the ineffectiveness of that measure, it really is no reason to pout.

But Hamburg has Olaf Scholz as First Mayor. The social democrat governs in line with city traditions – good for the economy and without making too much noise. If Scholz had it his way, road transportation would be just as quiet as he is. There are only a handful of politicians who are as openly for the energy turnaround involving private transport and transport of goods by road. Moreover, he is an expert on the subject.

The combination of economic strength and political will could make Hamburg the flagship city for electric mobility. Which is already true in some cases.

Hydrogen? No problem.

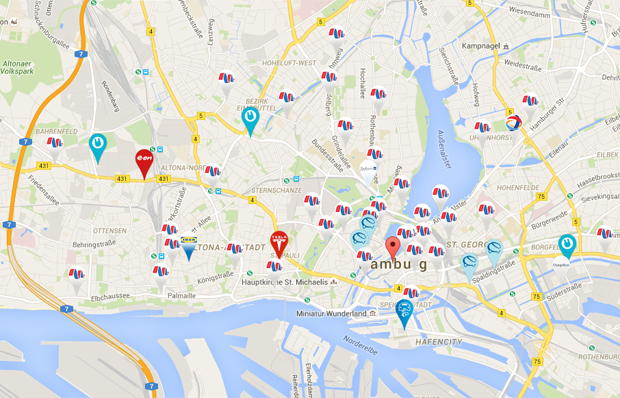

Drivers of fuel cell vehicles can fill up at one of four H2 fuelling stations in the city. Shell operates two of them, Toyota one and Vattenfall another. It is no coincidence that German’s first Toyota Mirai was delivered to a ship owner. On top of that, buses with hybrid, plug-in hybrid and fuel cell drivetrains are in service on line 109 – also called innovation line.

Hydrogen is a clear success story in Hamburg that can be checked off with one paragraph. Charging infrastructure for battery electric vehicles is a whole other story. Development is positive, but growth remains slow.

Local grid operator Stromnetz Hamburg (the city re-bough all power lines from Vattenfall) told electrive.com that as of January, Hamburg has some 85 charging stations with around 170 charging points. The goal is to have 600 by this autumn. To start charging, one only needs a text message, a RFID card (Ladenetz) or a key phob (The New Motion, PlugSurfing). Registered users of those three operators can charge in Hamburg as they would in any other city. Moreover, anyone can activate a charger via text message. Most AC chargers have an output of 22 kW. There are only three DC chargers – too few in a world that buys more and more EVs capable of DC charging and where time to plug-in is limited.

Between sanction and privilege

Yes, many charging locations now have a sign saying “2 hrs max.” For obvious reasons. Because on top of combustion engine cars blocking chargers, some electric car drivers used to treat the reserved spots as their private parking stalls. According to police, ICE vehicles can now at least be towed. That used to be different.

EV drivers do enjoy one perk when it comes to paid parking. If they have a license plate for electric vehicles (marked with an E at the end), they do not have to pay and can leave their car for the maximum time allowed.

That measure brings about another dilemma, which other cities face as well. It is clear that the will and the means to push electrification are there, but free parking can only be an in-between solution until the day that there are too many cars with a plug. And the possibility to open up bus lanes for EVs was struck down immediately. The city probably did not want some of its more well off citizens in Teslas and BMW i8 blocking public transport.

But back to the money and the will: both are there. There are numerous ways to incentivise electrification. One example is Hamburg’s bank of investment, the Hamburgische Investitions- und Förderbank (IFB). It pays up to 10,000 euros for the installation of a DC triple-charger, 3,000 euros for an AC charger and 3,500 if a location as at least four wallboxes.

It seems quite simple to get funding for a good cause. Those who take initiative preach to the converted and can count on a well-organised network.

While H2 stations are up and running, EV drivers looking to use public infrastructure have to be patient – especially if they want to plug in at DC charger.

Doubting public infrastructure

There is a fundamental problem. Charging battery electric vehicles works everywhere where there is space. Say in Hamburg’s exurbs, rich suburbs and smaller towns, where purchasing power is as high as the curiosity for new technology. The same is true at the office or all other partially public areas. Which is why electric driving starts with the commuter.

The last that electric mobility will reach will most likely be people living in highly populated parts of the city, where every evening they have to fight for a parking stall. It will be years before battery electric vehicles will be affordable and infrastructure sufficient – and there is no guarantee that we will ever get there.

Waiting for the electric Porsche

Hamburg’s Senate is laying the best and most essential groundwork in the country. And no local politician can change that there are still too few EV models on the market, that out of 44 million cars on the road, only three million are replaced every year, nor that only handful of those have an electric motor.

There is light at the end of tunnel. While it may still be cool to drive a V8 with a stripped exhaust on the arterial roads, many in the more noble districts prefer a Tesla. Moreover, no area in Germany has as many Porsche as Hamburg. Meaning that once Stuttgart-Zuffenhausen begins cranking out the Mission E, we could see even more electric mobility. And these drivers have access to the most import of all charging points – the one in their own garage.

Text: Christoph M. Schwarzer

Translation: Carla Westerheide

Picture credits keyvisual:

© morena / fotolia.com (background)

© Gunnar Assmy / fotolila.com (car)

© sester1848 / fotolia.com (town sign)

0 Comments